Over the last few years, the Oscars have had their fair share of notable, eye-catching moments, from Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway’s little oopsie when they inadvertently announced the wrong winner for Best Picture to “Parasite” dominating to Will Smith and the infamous slap. But while moments like “La La Land” briefly taking the Best Picture Oscar from “Moonlight” are as unforgettable as they are awkward, they only tiptoe so close to the precipice of absolute, wild insanity. It’s not as if “La La Land” actually did steal an Oscar away, for example. And it’s not as if a film or person has won an Oscar only to lose it.

As unprecedented as that sounds, though, you only have to cast your gaze as far back as the 1969 Oscars ceremony to glimpse some truly jaw-dropping one-time events. For instance, that’s the year when the Best Actress Oscar went to two people: Katharine Hepburn and Barbra Streisand, in the only acting tie in Oscar history. Oh, and it’s also the year that a film won an Oscar … and then had it rescinded. That dubious honor goes to the documentary “Young Americans,” which may well be why you almost certainly haven’t heard of this situation. It would be one thing if a more major release came so close to Oscar glory and had it wrested away from them; it’s something else for a film with a less recognizable background to have its victory revoked.

An Oscar-winning documentary was disqualified for a painfully simple reason

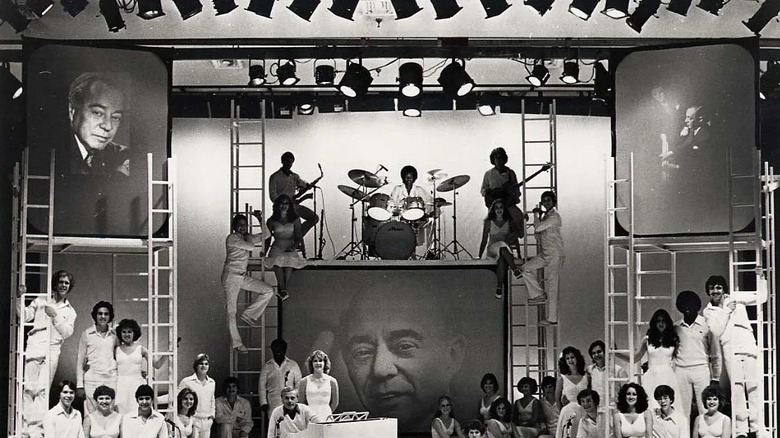

If you pay attention to the ins and outs of the Oscars each year, you know that eligibility is a very tricky thing. For example, a film like “Toy Story” is nominated for Best Original Screenplay because it’s not based on pre-existing material (even if it does reference real-life toys). But its 2010 threequel “Toy Story 3” was nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay, in spite of not being based on a book or other material aside from its predecessors. But one of the easiest definitions of annual eligibility is simple enough: a film has to play in a movie theater in the United States for at least one week in the year in which it’s nominated. If, for instance, the Sean Baker film “Anora” had been shown at a movie theater for a week in 2022, it couldn’t be eligible for the 2024 Oscars. That seems pretty straightforward, and yet, it wasn’t the case for “Young Americans.” The upbeat documentary from the late director Alex Grasshoff focused on a youth show choir of the same name as they prepare to tour the United States by bus. No doubt the wholesome topic and tone of the documentary made for a bracing counterargument to the upheaval in the United States in the late 1960s surrounding protests against the Vietnam War and the fight for civil rights. Instead of young people involved in those protests, here was a film about chipper and happy-seeming kids that would be easy to swallow for the Academy.

That may well be why “Young Americans” won the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature, but there was just one problem: the film had played at a small theater in North Carolina in 1967, a year before the film’s eligibility for the subsequent Oscars ceremony. Now, we can wonder about why the Academy didn’t realize the film should have been disqualified from the start, but such was the case. Although Grasshoff and his wife were able to enjoy an immediate honeymoon with the Oscar statue, they were soon contacted by none other than Atticus Finch himself, Gregory Peck (who was then the President of the Academy), and informed that they needed to return the statue with the honor revoked. When Grasshoff passed away in 2008, his widow spoke with the Los Angeles Times about the unique circumstances of winning and then losing the Oscar, saying that “it was a major disappointment” that stemmed from the fact that “Young Americans” had, in October 1967, had “a trial sneak preview in some little town.” It was enough for the Academy to take the award back, as extreme as it sounds.

Young Americans is a cautionary tale about the Academy enforcing its rules no matter what

It’s easy to roll our eyes at the Oscars and their rules sometimes, but they do stick to their guns no matter who is affected. A few years after the “Young Americans” debacle, they had to institute a second vote for the Best Original Dramatic Score Oscar because one of that year’s candidates was found to have re-used a theme from a late-1950s release. The offending film and score? Why, that would be “The Godfather,” with a score composed by the incomparable Nino Rota. If the Academy was willing to refuse to award the score from one of that year’s most massive and beloved films (and a score that, let’s not forget, is one of the greatest of all time), then it’s no surprise that they would uphold the same kind of toughness for a film that wasn’t nearly as famous. And those rules extend to high-ranking members of the Academy, too. In 2014, the composer Bruce Broughton was found to have used his influence as a former Academy governor to convince voters to nominate him for his song from the film “Alone Yet Not Alone;” once his vote-whipping was revealed, his nomination was rescinded. (Granted, this was the same year that “Let It Go” won the Best Original Song Oscar, so it’s not as if this other song had a fighting chance. But still.)

In spite of the dubious honor of winning and then losing an Oscar, Alex Grasshoff continued to have a fruitful career in the industry. He would go on to direct episodes of a handful of ’70s-era TV series such as “Kolchak: The Night Stalker” and “CHiPs,” as well as helm a few more documentaries such as the 1973 film “Journey to the Outer Limits.” (That film netted a Best Documentary Feature nomination, though it did not win.) He also won an Emmy and a Peabody for his 1981 film “The Wave” about a real-life experiment by a schoolteacher to show just how disturbingly easy it would be for people to accept the rule of the Nazi regime. Though Grasshoff’s name will always be synonymous with this odd little Oscars quirk, it didn’t sink his career at all. Decades later, we can only remind ourselves that as memorable as the Oscars can be, and as many slip-ups as they may make (sometimes in the biggest public setting), they always stick by their rules, expectations be damned.

Leave a Reply