Frank Herbert’s 1965 “Dune” novel has been a colossal inspiration since its release, encouraging countless other authors and filmmakers. However, for years, a successful movie adaptation proved very hard to get it right. Over five decades later, we have Denis Villeneuve’s “Dune: Part One” and “Dune: Part Two,” satisfying critics, fans, and the Academy.

While we wait for “Dune: Part Three,” what’s a fan to do? Well, the influences of “Dune” go far and wide, as do the cinematic influences of director Villeneuve. From the movies that were inspired by Herbert’s original novel, to other films that capture something of the spirit or style of the story, and even previous attempts at tackling the material, there’s a lot of cinema out there to please fans of the young, selectively bred Messiah figure Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet), who joins the desert-dwelling Fremen on spice planet Arrakis and quells the feud between House Atreides and House Harkonnen. By marrying the Emperor’s daughter, Paul seems to momentarily appease the royal houses and the zealous, nun-like Bene Gesserit, but he might have just ignited a larger war over the valuable spice Melange, which can empower space navigators and induce visions.

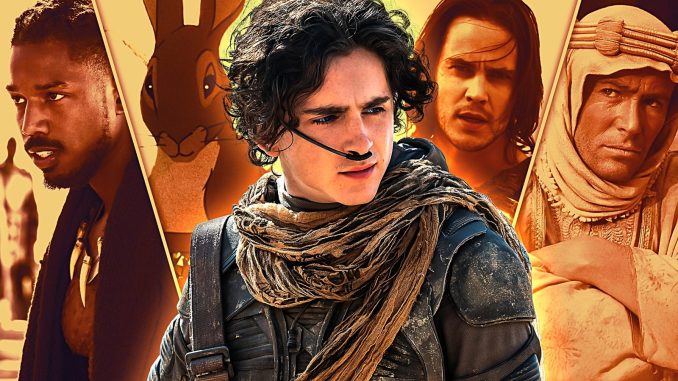

Taking both films as a whole, here are the 15 best movies that resemble Villeneuve’s “Dune.”

Dune (1984)

It’s tough to get any more like “Dune” than another version of “Dune,” though David Lynch’s 1984 version looks really different, thanks to production design by Anthony Masters (“2001: A Space Odyssey”) and costumes by Bob Ringwood (“Batman”), which makes it look like an epic goth bondage ball in space. Producer Dino De Laurentiis clearly wanted his own sci-fi franchise for the whole family like “Star Wars,” and 1980’s “Flash Gordon” hadn’t been it, but he reckoned without the subversive nature of the source material. Without final cut or the strength of being the renowned auteur he became later (the failure of 1984’s “Dune” taught Lynch a valuable lesson), the director delivered a version that relied too much on voice-over, and buried the irony into deep subtext. Without reading the novel, one can watch this version and conclude it’s a sincere Messiah story.

Still, Lynch’s “Dune” boasts an incredibly distinctive look. It also successfully a blended cast of A-listers and future stars (Jose Ferrer, Sting, Virginia Madsen, Sean Young, Patrick Stewart, Max von Sydow) alongside Lynch regulars (Kyle MacLachlan, Everett McGill, Jack Nance, Dean Stockwell). The fact that the film works pretty well as an adaptation to those who have read the book and know everything the film doesn’t have time to tell means 1984’s “Dune” stands today not as the epic failure it was once considered, but a cult classic and a fascinating parallel universe to Villeneuve’s version.

Lawrence of Arabia

“Dune” author Frank Herbert drew inspiration from the life of the real T.E. Lawrence, so it only makes sense that Denis Villeneuve would also draw inspiration from the epic David Lean cinematic masterpiece that told his life story. In the movie, Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) is a British army officer sent to assist Iraqi Prince Faisal against the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Winning over the locals with tactics and bravery, he also stands up for them against his own superiors. As he integrates more into the local culture and develops a white savior complex, with the help of the media making him a hero, he begins to get more bloodthirsty, and push for an Arabian independent state.

Though its historical accuracy has been disputed, “Lawrence of Arabia” became a big hit and an instant classic, a favorite of filmmakers from Akira Kurosawa to George Lucas, and it set a precedent for the kind of desert battle scenes shown in “Dune.” Paul Atreides is more victorious than Lawrence, but his path is just as fraught with moral ambiguity, trade-offs, Colonialist baggage, and a Messianic image that helps and hurts his cause. (The “Lawrence of Arabia” ending, explained.)

Avatar

“Avatar” often gets dinged by its critics for unoriginality, though its epic, imaginative spectacle more than makes up for it. “Dune,” the novel, is one of its most obvious source of inspiration: both feature a planet rich in a resource found nowhere else, and a hero from a colonizing power who turns to the side of the indigenous people, falls for a local tribeswoman, and fulfills an ancient prophecy. Whether you prefer Pandora to Arrakis is a matter of taste — desert, or bioluminescent jungle?

Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) isn’t as complex a character as Paul; he’s a Marine doing a job who falls in love, and he only fulfills the prophecy of Toruk Makto by combining his training as both a human Marine and a Na’vi warrior, to come up with an inventive solution that neither side individually considered. However, as in Paul’s case, it involves learning to ride and tame the biggest native beast around.

John Carter

Tarzan may be our most classic pop cultural myth about a child of aristocracy who goes native to become a hero and leader in his new environment, but it’s the other famous creation of Edgar Rice Burroughs, John Carter of Mars, who likely inspired Frank Herbert’s “Dune” more.

In 2011, Disney’s big-budget film adaptation, starring Taylor Kitsch in the title role of “John Carter,” didn’t prove as inspirational, and flopped after a lackluster promotional campaign that was afraid to say the word “Mars.” Audiences felt it was derivative, even though many of the things the film might have felt derivative of — like, say, “Attack of the Clones” — had been inspired by the John Carter books in the first place.

“Dune” added many more layers to the story, but the fundamental tale is already there. It’s one of warring dynasties on a desert planet, and an outsider with super-abilities who leads an alien tribe in rebellion against their hegemony, culminating in a royal wedding that brings a temporary peace (until the inevitable sequels, which happened in print but not onscreen).

The Ten Commandments (1956)

There is no more classic, epic film about a religious figure leading his tribe through the desert to thwart a bald tyrant than “The Ten Commandments,” with Charlton Heston as Old Testament prophet Moses and Yul Brynner as Pharaoh Ramses II. Adjusted for inflation, it’s the eighth most successful film of all time, and Cecil B. DeMille’s second take on the material. (The first version, a silent black-and-white take, divides its run-time between the Moses story and a then-modern-day tale of corruption in the construction business, so it’s not quite as “Dune”-like.)

With epic sets, groundbreaking-for-the-time visual effects, and even some uncharacteristic Biblical roles for Vincent Price and Edward G. Robinson, “The Ten Commandments” is so ensconced in our collective pop-culture consciousness that Charlton Heston is now who most people think of when they envision Moses. The movie also has more layers than just the Bible story — in a rarely seen filmed introduction, DeMille addressed audiences to state that he hoped they saw parallels between the persecuted Israelites trying to escape tyranny and the people of Eastern Europe dreaming of escaping Soviet Communism. “Dune” similarly draws equally on Middle Eastern conflicts and religious tropes.

Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace

Unusually among Messianic figures in fiction and mythology, Paul is biologically bred to fit the savior mold, the product of years of genetic tinkering, albeit born too soon. There’s another Chosen One in sci-fi whose blood analysis proves his status, and that’s Anakin Skywalker (Jake Lloyd), discovered on a different desert planet in the first “Star Wars” prequel.

We know he was born of a virgin, but was he genetically created by Darth Plagueis and Sheev Palpatine? Lucasfilm’s official stance is that that issue will always be left unclear. One thing we do know is that, much like Paul Atreides, Anakin grows up to do a lot of killing, break his lover’s heart, and take a darker path than a savior in scripture typically does. All despite having more Force-amplifying “midichlorians” in his bloodstream than even the great Master Yoda.

In a fight, the forward-thinking Bene Gesserit would wipe the floor with the mostly useless Jedi Council, though.

Black Panther

Like the planet Arrakis, the nation of Wakanda in “Black Panther” is rich in a rare resource that gives any nation who controls it a decided advantage in governmental power struggles. Vibranium, like the spice Melange, powers futuristic technology, while the heart-shaped herb that’s infused with it gives the monarch superhero incredible powers. Unfortunately for all concerned, in both cases stewardship can be taken by force. Whether it’s the Harkonnens invading Arrakis under Atreides leadership, or Killmonger (Michael B. Jordan) defeating King T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman) for control of the valuable substance, the people suffer when evil strongmen take charge, and assert the reigns of power.

T’Challa and Killmonger arguably represent the two different paths Paul Atreides can take. Use the power of his position to engage the larger universe, or make war, however righteously motivated, on all of it? In the sequels to both “Dune” and “Black Panther,” we learn that perhaps the protagonist’s younger sister will be the more powerful hero to eventually take charge, after all.

Blade Runner 2049

Storywise, “Blade Runner 2049” isn’t a lot like “Dune.” It’s rainy rather than dry, its protagonist (Ryan Gosling) is a slightly clueless non-savior, and the mission is more philosophical than political. Yet both films feature the moody, atmospheric touch of director Denis Villeneuve, and this was the one that proved to Warner Bros. that yes, he is the guy who can be trusted to do beautiful, respectful things with valuable sci-fi IP. The man who made “Sicario” can handle massive, futurescape word building.

Released in 1982, “Blade Runner” wasn’t a hit at the time. Over the years it gained in respectability, particularly for its ground-breaking production design.

A sequel was contemplated for years, though it faced a major dilemma: how to deal with the big unanswered question of whether or not Ford’s Rick Deckard was really an android Replicant? Villeneuve never fully answers that question in his sequel, keeping the mystery alive while opening new possibilities and considering new issues confronting artificial intelligence. That’s the kind of deft touch a new take on “Dune” was going to need.

Wonka

Timothée Chalamet arrives in a desolate land, where he unites the lower classes in rebellion against profiteers, with an assist from a strange creature and an addictive substance with near-supernatural qualities. One day, however, we know his abilities and power will make a target and a loner with megalomaniacal tendencies. “Dune”? Not this time. It’s hard not to notice that Chalamet’s Paul Atreides has a lot in common with his Willy Wonka.

Chocolate in real life may be the closest thing to magical space spice, but as Roald Dahl’s books established, Wonka’s abilities as a candy-maker transcend normal laws of physics, whether they make a person fly or blow up like a blueberry. In the fantasy-Dickensian world of the musical “Wonka,” he who controls this chocolate controls the universe…or at least Britain. The chocolate must flow, and young Wonka becomes a hero, but because we know that this is explicitly a prequel to the Gene Wilder-starring “Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory,” things will change.

Immaculate

The Bene Gesserit of “Dune” want to breed a Messiah using a slow breeding process across many generations. The nuns in “Immaculate” don’t the same kind of patience. They want their clone savior now, which is bad news for Sydney Sweeney’s Sister Cecilia. Unbeknownst to her, she’s the latest chosen vessel for a genetically enhanced virgin birth.

“What if the Bene Gesserit were evil?” may be a redundant theme from a certain point of view, but using their basic underlying premise as the basis for a horror movie is smart, because they’re scary. The approach used in “Immaculate” is a little different scientifically. The convent possesses an original crucifixion nail, and they hope to clone Jesus from it. The problem is, as with “Dune,” that you can’t force the existence of an incarnate deity if no actual God endorses it. Instead, the result is bound to be an abomination, and indeed, they’ve tried several times.

There’s also the whole issue of consent, which Cecilia unequivocally revokes at the end of “Immaculate.”

Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes

In the post-apocalypse “Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes,” the Messiah figure, Caesar, is dead. Centuries later, deadly power struggles ensue.

Noa (Owen Teague) is a young chimp from a rural falconer clan who finds himself caught up in the conflict between smart humans, represented by the innocent-seeming but crafty Mae (Freya Allen), and violent apes, led by Proximus Caesar (Kevin Durand), whose size and grandiosity resemble Baron Harkonnen. As in “Dune,” it’s the little guy who’ll ultimately summon the strength and the allies to end the battle…but only for now. No “Planet of the Apes” movie gets to end without some sort of twist that anticipates possible future sequels, after all.

It’s a whole different biome from “Dune,” with jungle retaking the world, and Proxiumus’ base on the shoreline. Yet it’s once again the same struggle of conquering greed versus natives in harmony with nature, and the possible advantage a hidden resource — in this case, human weapons and research — can give to one side or the other.

Solaris (1972)

Fans of contemplative sci-fi with a protagonist prone to visions, as in much of “Dune,” should check out Andrei Tarkovsky’s moody masterpiece, sometimes considered to be the Soviet Union’s answer to “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Adapted from the Polish novel by Stanislaw Lem, “Solaris” is set aboard a space station, orbiting an ocean planet which appears to have the ability to induce hallucinations.

Scientist Kris Kelvin (Vladimir Zamansky) lost his wife Hari (Natalya Bondarchuk) ten years previously, so he’s shocked to encounter her aboard the station — or, at least, a perfect copy of her. The seemingly sentient oceans on the planet can create duplicates from the astronauts’ mind, but what happens when they become too self-aware, and realize they aren’t “real”? Or, indeed, are they as real as anybody else? If the parts of “Dune” that you prefer aren’t the big battles, but the moments where Paul trips out and dreams, this is the movie to follow it with.

The Steven Soderbergh remake starring George Clooney isn’t terrible, but it’s a lot more literal. To feel like you’ve actually drunk the water of life, go for the original Tarkovsky.

Watership Down

In the U.S., “Watership Down” is mostly known as the cartoon rabbit movie that traumatized kids who weren’t prepared for scenes of bunny-on-bunny violence. In the U.K., it’s simply the adaptation of Richard Adams’ popular novel for children, who are prepared for what they see if they’ve read the book first.

In any case, it’s a story that, if it were about humans instead, might resemble “Dune” quite a bit. It involves young rabbit Fiver (Richard Briers) receiving prophetic visions of doom for his warren, and escaping with a small group including leader Hazel (John Hurt) and warrior Bigwig (Michael Graham Cox). After several brushes with danger, they find their way to a safe base of operations, but come into conflict with a ruthless, fascist warren over control of the most important resource, which in this case is female rabbits. Okay, that sounds horribly sexist when framed as a human story, but because we’re talking about rabbits, which are literally the poster animals for excessive breeding, the movie gets away with it.

There’s also a healthy dose of rabbit theology involved. Adams made up the story as he went along as a bedtime tale for his children, so all the mythological, heroic, and religious subtext is ostensibly subconscious on his part, but it’s there.

Pitch Black

Imagine Austin Butler’s Feyd-Rautha Harkonnen surviving the events of “Dune” captured, and headed for justice on a prison planet when the spaceship crashes en route, on to another desert planet, and only he can keep the other passengers alive. That’s essentially the plot of “Pitch Black,” the movie that kickstarted Vin Diesel’s action hero phase of his career. It spawned two sequels, remaining the only Diesel-starring franchise in which he actually appears in every movie. “The Fast and the Furious” and “xXx” cannot claim the same, whereas both “Pitch Black” sequels — “The Chronicles of Riddick” and “Riddick” — center on Diesel’s titular lead antihero.

Richard B. Riddick is a criminal who can see in the dark, which helps when it comes to battling creatures who fear the sun and only come out at night. His universe, like that of “Dune,” is a complicated one beset by issues of religion and politics; look no further than the death-worshipping cult called the Necromongers, who seek to conquer the known universe.

Jodorowsky’s Dune

Lest anybody doubt that Denis Villeneuve pulled off a minor miracle in making two good movies out of “Dune,” Frank Pavich’s “Jodorowsky’s Dune” looks at the first major attempt to make a film of the book, when filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, best known for the surrealist western “El Topo,” threw his hat in the ring. This documentary chronicles how that process went, and it’s a tale of hubris worthy of the Harkonnens.

Jodorowsky shot for the moon. He wanted to cast Salvador Dali as the Emperor, and when Dali demanded $100,000 per hour, planned for just an hour of shooting time for him, with a robot stand-in in other scenes. Pink Floyd would do the soundtrack, with Mick Jagger playing Feyd-Rautha, Orson Welles as Baron Harkonnen, and Jodorowsky’s son Brontis as Paul. Moebius and H.R. Giger were set to do production design. Jodorowsky spent $2 million of the budget on preproduction, and his script, according to Frank Herbert, would have resulted in a 14-hour run time.

If Villeneuve’s film is the happy ending, Pavich’s documentary is the tragi-comedy that leads there.

Leave a Reply