Brooke Shields has spent a lot of her life being pleasant. As a preteen, she smiled courteously as journalists inquired about whether she felt oversexualized and exploited in films like 1978’s Pretty Baby and her instantly iconic Calvin Klein ads two years later. She was the dutiful daughter to her mother and manager, Teri, whose alcoholism made their close bond indescribably complex. She smiled for the cameras when they followed her to Princeton University in 1985 and asked (as if it were their business) about her being a virgin. Young Brooke Shields was a master of standing out and being sweet.

As she grew up, she continued to shine but used her voice more defiantly — most memorably in a 2005 New York Times op-ed response to Tom Cruise’s attack on her use of antidepressants during postpartum depression after the birth of her first daughter, Rowan. She showed her comedy chops in four seasons of her NBC sitcom, Suddenly Susan, and multiple Broadway shows. She published two New York Times bestselling memoirs.

Then she had the nerve to do something (apparently) unexpected: She kept getting older. Though her confidence and joy grew as she aged — she turns 60 this spring — she writes in her new book, Brooke Shields Is Not Allowed to Get Old: Thoughts on Aging as a Woman (on sale Tuesday, January 14), “I began to notice that external perceptions didn’t seem to match up with my internal sense of self. My industry no longer received me with the same enthusiasm I had come to expect. The vibe from casting agents and producers, but also my fans, was more: You need to stop time… and maybe even reverse it.”

To borrow a phrase from her book, f— that. Frustrated by “being overlooked at the exact moment I was feeling in my prime,” as she writes, she added a new entry to her résumé in 2024: founder and CEO of Commence, an online community and haircare brand designed for women over 40.

“The more I’m expected to be invisible, to make no demands or to fade away so that I can be frozen in time as a specific (read: younger) version of Brooke Shields,” she writes, “the more fully I intend to stand tall and take up space as the woman I am now.” The star once known as America’s sweetheart talks to Us about stepping into her power.

The book opens with you and your daughters, Rowan, now 21, and Grier, 18, walking down the street and your realization that people are staring at them, not you. Tell Us about that.

The conflicts that we feel — they hit you all at once. There’s such protection, such pride and joy, and then it’s a reflection back on what you are no longer, technically. And I’m not saying there’s an envy or jealousy, but it’s a restructuring: They’re starting their journey as you’re reaching a level that is hopefully [more] happy and calm but comes with a lot of fraught feelings.

It’s the perfect setup for something you write later in the book: “When men stop noticing you, it’s a pretty good indicator of how the world at large is going to treat you.”

To me, I think anybody who has a daughter in particular can identify with: Oh, my God, I’m not that anymore. What is my value now?

You talk about learning to use invisibility to your advantage — letting people underestimate you and then capitalizing on that.

If you don’t get angry at it and find a way to harness it, it’s a tool. It’s funny, my girls are all righteous about these things: “How could you say that, Mom?” I’ll say, “My ego doesn’t have a problem with playing this game. I’m weakening my opponent into thinking I’m incapable.” I found it a source of definite power and strength.

I used to apologize or start off with “I’m probably wrong, but …” or, “Do you think possibly …?” I don’t have to come in weak anymore. And then I don’t have to finish it with, “But you know better.”

How have you learned to navigate these conversations?

You can defer and be respectful. Often I say, “This is your area of expertise, and I do not pretend to know a percentage of what you do, but in my opinion…” Then I’m a bit more on equal footing, and I don’t feel like I have to diminish myself to express something, whereas I think I used to be afraid to have an opinion.

So many women are more comfortable and confident in their 40s and 50s. Why is there this notion that women in middle age are completely miserable?

Because they have told us we’re miserable. And so if you even look at the nature of commercials, right, it’s always like, “Do you have dry skin? Are you this? Womp-womp.” That’s what the narrative is, and the beauty company, pharmaceutical or whatever it is, they’re going to come in and solve all your problems for you. Because if you’re happy, well, what if you don’t need their dry-skin cream? So it’s this whole conspiracy we’ve been fed.

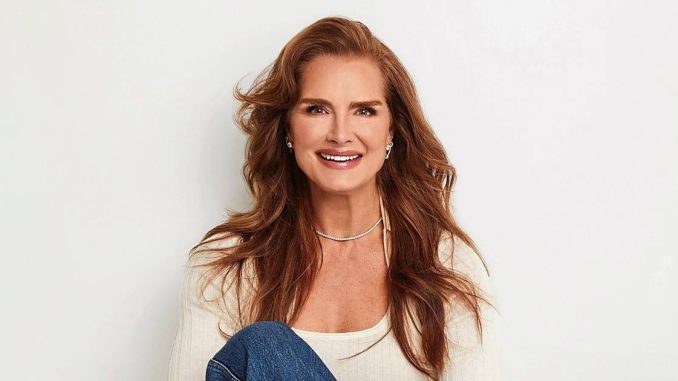

Brooke Shields. Deborah Feingold

That’s totally right.

Yes, [aging] does have the downsides, but [we’re] no longer chasing something: gotta have babies by this age, gotta get married, gotta finish college. There are so many decades where we’re just trying to get to the next stage. And then there’s a shift.

Once the pressure is off, you note, older women are more able to be themselves: “We can push boundaries when we’re moving through the world without the watchful eyes of, well, everyone.”

It doesn’t mean I’m less ambitious. If anything, I’m probably more ambitious because I feel I deserve it more. I still get afraid. I still get nervous I’m not good enough. I still have to force myself to push through, [but] we are becoming unignorable. We’re pretty formidable, and I think that’s a little frightening for everybody.

It takes a different kind of strength to allow yourself the grace to say no — for example, you declined an invitation to perform alongside Broadway powerhouse Cynthia Erivo and Susan Boyle of Britain’s Got Talent. How do you decide when to say no to what seems like — to everyone else, at least — a golden opportunity?

There’s a sense of healthy humility, [of] why would you want to do that to yourself? It’s not, I’m “less than” as a person, but there’s no way my capabilities reach theirs. I used to think if I was just good enough, I would go and at least hold my own, and that would be a feat in and of itself. But you have to say, “I don’t want that feeling in my stomach that I would undoubtedly feel.”

You devote a chapter to becoming an empty nester as first one, then both of your daughters left for Wake Forest University in North Carolina. “My girls have a lot of skills I never did,” you write. Have you worked to guide them away from habits you don’t love in yourself, such as people-pleasing?

I have one that’s very much a people pleaser, and I have a younger one who’s about right and wrong, and it doesn’t matter what people think. She’s very strong in her opinions. Even her reactions — I will say, “Aren’t you embarrassed?” And she’s like, “No. No, I am not.” And she’s 18, maybe she’ll feel differently. My older one really does straddle that, and I don’t know if it’s age, birth [order], whatever — we are the most similar, in our approach to life and our actions.

I’m so proud that I have cleared space for them to be able to contradict me, express their feelings and not be afraid they’re gonna be judged. And being OK if I don’t agree with them. They just have different ways of expressing it to me.

One thing that is so specific to you is how much of your life has been documented. What is it like to look back and see the girl you once were, who was under so much scrutiny?

I have such empathy. My heart just sort of swells for her and her desperate, desperate need to protect her mom and take care of everything. It felt like it just was what I was gonna do.

And today?

I see myself now [at Commence HQ], and I never aspired to be in a position like this. I think about the Zoom I had this morning with one of our investors, and how clear I was for that; and how I was in therapy an hour before; and how I’m navigating my kids; and how I’m helping my husband through something; and you just see all of these different spokes of a woman’s wheel, you know? There’s pride, because I don’t give a s— if someone doesn’t like me anymore. I mean, yeah, you get the little pang, but I sit back and I think, I don’t even know if I respect you, so why would I worry so much about you liking me?

Leave a Reply