How often have we all heard audiences leave the theater after watching a new cinematic adaptation of a novel, grumbling to themselves that the book was better? Often, readers get very attached to a specific novel, and any attempts to adapt it for the big screen are doomed to failure. After all, books are able to delve into a narrative with so much more depth, and films, limited by their runtime, have to consolidate or rearrange story elements to make them fit properly.

But every once in a while, the reverse happens. A film is actually able to improve on what was put forth on paper. Sometimes this is because a story is particularly well-suited for a more visual medium, and sometimes it just finds itself in the hands of an unusually talented director. But these projects are worth celebrating because when a filmmaker adapts a book for the big screen, they’ve reached rarefied air indeed.

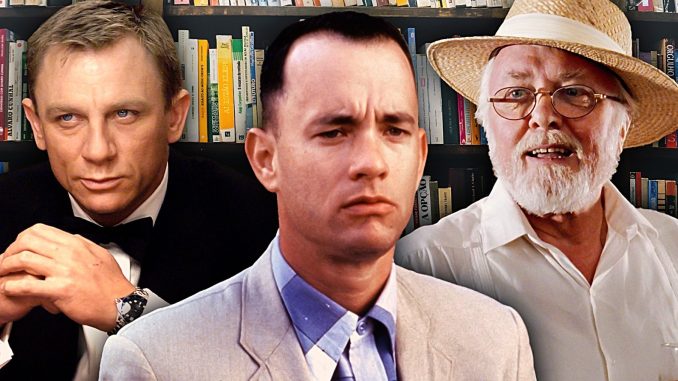

Jurassic Park

Look, both the book and film version of “Jurassic Park” — the cautionary tale of a misguided theme park filled with hordes of bloodthirsty dinosaurs just itching to break free from their enclosures — are winners. When Michael Crichton released his now-famous novel, it was so popular that it even launched a massive bidding war between Hollywood studios for the rights to turn it into a movie. Choosing between the two is going to come down to a preference of tone. Michael Crichton’s novel is much more circumspect than the film, detailing the perils of putting too much blind trust in technology, whereas the film is … well, an action-adventure flick with the oldest narrative conflict of them all: Man vs. Dinosaur.

But beyond the difference in approach between the book and film, it has to be said that the story is served so much better by the cinematic medium. Especially with the endlessly inventive Steven Spielberg behind the camera, using ’90s special effects so efficiently as to make the exploits of “Jurassic Park,” despite being released over 30 years ago, hold up to this day. CGI may have grown more advanced since 1993, but you don’t need state-of-the-art computer effects to expertly build tension: You just need a pair of kids and a paleontologist scrambling down a tree, narrowly avoiding a car crashing down on them.

Psycho

Honestly, the legacy of Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” is so firmly rooted in popular culture that most people probably don’t even realize that it began life as a book. (No disrespect to Robert Bloch, who wrote the original novel that was released in 1959, a year before Hitchcock made cinematic history with his adaptation, of course.) But when it comes to the dark, profoundly disturbing story of Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and Marion Crane (Janet Leigh), the woman unlucky enough to cross his path, the film is the superior beast.

The success of “Psycho” has a lot to do with Hitchcock’s legendary ability behind the camera, but we also have to extend credit to his marvelous screenwriter, Joseph Stefano. In adapting the original novel, he shifts the initial focus from Norman to Marion, which accomplishes two key things. First, it makes the audience more emotionally connected to Marion, who is a much flatter character in the book. But more importantly, it allows for the gut punch of her death, when we had assumed that she was going to be the film’s protagonist, only to be entirely wrong-footed when she’s shockingly killed off an hour into “Psycho” — a twist that convinced Hitchcock to take on the project in the first place.

Jaws

The movie “Jaws” probably can’t be considered to have single-handedly launched the revival of the blockbuster in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, but it certainly played an outsized role in it. The book, by contrast, is often forgotten. There are plenty of reasons for this — the mere visual power of Bruce the shark alone is enough to wipe any literary predecessor from the minds of audiences. But to be honest, Steven Spielberg and his team simply do an excellent job of taking the kernels of what work in Peter Benchley’s “Jaws,” and excising everything else.

We probably don’t need, for example, large swathes of background information about fishing, or scandalous morsels about Chief Brody’s (Roy Scheider) wife’s affair. Spielberg realizes, rightly, that for “Jaws” to be successful, it has to cut right to the guts of the matter, with that ominous fin poking out of the water. (And all of this is to say nothing of how drastically different the endings of the book and the movie are.)

There’s one more thing that puts the movie “Jaws” head and shoulders above the novel, and to be fair, it’s not even Benchley’s fault. You know what movies have that books don’t? Music. Even if everything else were equal, John Williams’ iconic score would put the movie over the top.

Forrest Gump

Over the years since its initial release, “Forrest Gump” has undergone something of a critical reevaluation. Some consider it to be a placid suggestion that the best way to achieve success in America is to be a moderate white man who is content to go with the flow and simply allow history to happen around him, whereas Jenny (Robin Wright) is punished for actively engaging on the world, especially its counterculture. But whatever political undertones there may be in “Forrest Gump,” it’s hard to ignore the pure heart that director Robert Zemeckis and star Tom Hanks pour into the proceedings, which made audiences fall in love with it in the first place.

Whatever charms “Forrest Gump” has, however, are largely absent in Winston Groom’s original 1986 book the film is based on. The titular character is much less winsome and much more aggressive, sapping him of the innocence that makes him, frankly, worth rooting for. And while some of the situations that Forrest finds himself in during the film are admittedly outlandish, the book goes even further — it even sends him to space as an astronaut, stretching credulity well past the breaking point.

Casino Royale

James Bond has become a cinematic institution since he was first adapted for the big screen in the early 1960s, thanks in large part to the vision of author Ian Fleming, the creator of the book series and himself an intelligence agent during World War II. He essentially defined the image of the debonair, cool-under-pressure spy, a character who has been brought to life by a handful of different actors, each bringing their own unique spin to the role. The latest in the long line of Bonds was Daniel Craig, who made his on-screen debut in “Casino Royale,” a cinematic outing that gave audiences a glimpse of a grittier, less polished version of the beloved secret agent, and is considered by many to be one of the best James Bond films.

“Casino Royale” was actually the first James Bond novel to come out back in 1953, and while it perfectly sets the stage for the now iconic character, it also, well … hasn’t aged particularly well. Bond has always had a reputation for being a bit of a womanizer, but the misogyny in the original novel is on a whole different level. Obviously, everything has to be viewed through the cultural lens of the time it was made, but it makes it a little harder to recommend the book when Craig’s “Casino Royale” is even just a few ounces more enlightened.

Lord of the Rings

If you hold your laptop really close to your ear, you might be able to hear the combined, audible fury from “Lord of the Rings” fans in finding their beloved piece of fiction on this list. But hold your horses, and hear us out.

“Lord of the Rings” by J.R.R. Tolkien is an excellent trilogy. Its epic battle of good and evil playing out between humble Hobbits, ethereal Elves, earthy Dwarves, and easily corruptible Men is the kind of literary work that attracts generations of devoted readers, as we’ve plainly seen in the reaction to “Lord of the Rings.” But it’s also bogged down in a lot of mythology and asides — stuff that is catnip for the type of fans who would gladly savor every morsel of additional content Tolkien could serve up. It has the type of meandering plot — with so many bits and bobs that are tangential to the story at best but still quite fun — that makes it especially cumbersome if someone were to adapt it for the big screen. So the fact that Peter Jackson was able to not only make a coherent film series out of “Lord of the Rings,” but cobble together what might be one of the most spiritually faithful, genuinely entertaining adaptations that can go toe to toe with the source material — that’s kind of a miracle.

The Shawshank Redemption

There’s a sizable contingent of movie fans who would make the argument that Stephen King’s short stories end up making better films than his full-length novels, and “The Shawshank Redemption” is a solid point in their favor. Based on his 1982 novella “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption,” the popular 1994 prison drama stars Tim Robbins as Andy Dufresne, who has been imprisoned for allegedly murdering his unfaithful wife — a crime he didn’t actually commit.

Although the short story is worth a read in its own right, the film is able to flesh out the themes it doesn’t have time to fully expand upon. “The Shawshank Redemption” also benefits from exceptional performances from both Robbins and his co-star Morgan Freeman, who plays Red, a prisoner who has been at Shawshank so long he essentially has the run of the place. It received several nominations at the Academy Awards, including best picture, best actor (Morgan Freeman), and best adapted screenplay — which, if nothing else, speaks to the quality of the script based on King’s work.

Children of Men

Alfonso Cuaron’s dystopian drama about a world where humanity has lost the ability to reproduce immediately won over audiences with its haunting depiction of a society staring down its own extinction and, almost more importantly, how quickly society begins to deteriorate when it recognizes it has no future. “Children of Men” stars Clive Owen as Theo, a grieving father and disillusioned former activist who finds himself tasked with protecting a young woman who has miraculously found herself pregnant — the first known pregnancy in nearly two decades.

Where Cuaron zooms in on the one specific moment within a larger narrative, creating a sense of immediacy with his explosive, innovatively framed action set pieces, the original novel “Children of Men” by P.D. James devotes much more time to world-building, exploring social movements and particularly the conflict between the youngest (and presumably last) generation and their elders. While this is all fascinating, Cuaron is able to capture the most compelling aspects of the story, creating a film that is no less thought-provoking for being action-packed.

Stardust

Neil Gaiman has made a career out of developing the fantasy genre, transforming it into something lighter and much funnier than audiences were trained to expect. This is certainly true of “Stardust,” his novel about a young man (“Daredevil” star Charlie Cox in the movie) who goes on an adventure over the Wall into the magical realm in pursuit of a fallen star to bring back to his beloved. The original story is inventive and entertaining enough, but in the capable hands of screenwriter Jane Goldman and director Matthew Vaughn, it’s able to become so much more.

First of all, they tweak the lead character’s name from Tristran to Tristan; that’s a small detail, but the change is infinitely softer on the ears. Goldman seems to embrace the spirit of the novel but also knows when to run with her own ideas, creating the entire subplot of the ship that captures lightning from the sky and the delightful character of Captain Shakespeare (Robert De Niro). And perhaps most importantly, she fleshes out the character arc of Tristan, making the audience infinitely more invested in his plight and deepening his romantic subplot with Yvaine (Claire Danes) in the process. It’s this rich texture that makes “Stardust” such an enduringly magical fantasy cult classic.

The Godfather

This one’s not quite fair to Mario Puzo, we’re afraid. His version of “The Godfather” is good — really good, in fact — but it’s not one of the top five books ever written, and the same cannot be said of Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather” for films. Coppola turns Puzo’s pulpy crime drama into a sprawling family epic, one that doesn’t shy away from the shady dealings of the Corleones but also taps into something deeper and more emotionally evocative. Although it’s still a lengthy, somewhat unwieldy film — and that’s even before we address the two sequels — it cuts down on some of Puzo’s subplots that have a tendency to muddy the works.

Puzo also feels the need to use other characters to explicitly comment on the damage done by Don Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) and the world of organized crime in general, something the film accepts as understood by the audience without needing to spell out. And ultimately, “The Godfather” would be nothing without the towering presence of Don Vito — a character Puzo often undercuts by showing him through the eyes of characters who can see his weaknesses.

Leave a Reply