Spoilers for “Wolf Man” follow.

Stories of part-animal/part-human creatures go back to the dawn of humanity. One might immediately think of the beastly, hairy Enkidu, the rival-turned-friend of King Gilgamesh in the ancient Mesopotamian epic. When it comes to werewolves, however, our modern perceptions of the creatures come directly from Hollywood. The first major werewolf movie was Stuart Walker’s 1935 horror flick “Werewolf of London,” and it introduced a lot of what a modern pop audience associates with Wolf Men. The protagonist of “London” was a British botanist named Dr. Glendon (Henry Hull) who discovered a rare, moon-blooming planet in the hills of Tibet … right when he was bitten by a mysterious beast creature.

Back in London, Dr. Glendon makes a series of discoveries. For one, he learns that werewolves are real. He also finds that they transform around the time of a full moon. The plant he discovered is an antidote, and that the werewolf “virus” can be spread through a bite. He also finds that werewolves have to kill every night, otherwise they won’t transform back into humans.

Right from the jump, then, werewolves have been a curious mix of science and magic. There is something in werewolf saliva that “infects” a victim, causing them to become a werewolf themselves, but one’s werewolf-ism is also closely connected to full moons and murder curses. These tropes would be solidified in George Waggner’s 1941 classic “The Wolf Man” starring Lon Chaney, Jr. That film also featured a werewolf infection spread by a bite, but also a Romany curse, full moons, and curious mystical symbols. That film has become canonical in the realm of horror movies, and the Wolf Man is one of the champion Universal Monsters.

Leigh Whannell’s new film “Wolf Man” is a proper studio reboot of Waggner’s film, and it seems to skew away from traditional “curse” elements. This time around, the curse is more of a metaphor.

In the new Wolf Man, the curse is a metaphor

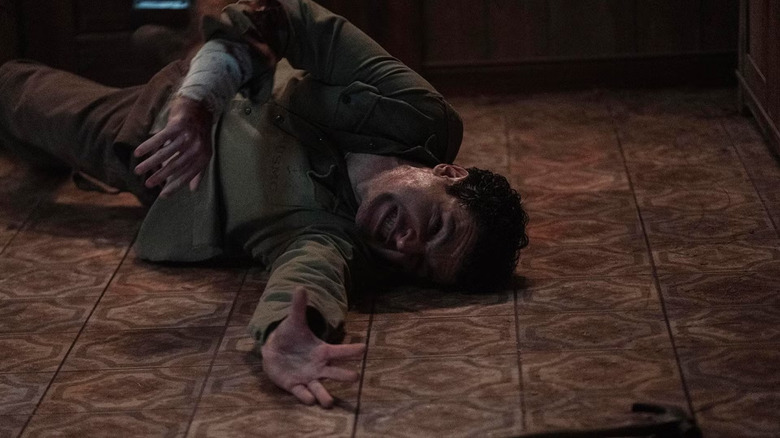

“Wolf Man” follows the life of Blake (Christopher Abbott) who was raised in a remote cabin in Oregon by a survivalist father. Blake’s father used to yell at him and berate him, constantly warning the boy that the woods are dangerous and that he needs to learn how to use a gun in order to survive. His father isn’t physically abusive, but he does have a temper. As an adult, Blake moves to the Big City and settles down with a wife (Julia Garner) and daughter (Matilda Firth). When his father dies, Blake is called back out to the cabin in the woods, having to claim it as inheritance. His family begrudgingly agrees to join, and they pack up a moving van for an extended Oregon stay. Naturally, there is … something … lurking in the woods when they arrive.

The something is a Wolf Man. This is a creature Blake had a run-in with as a child, and he recalls stories of a hiker that, back in 1995, became lost in the woods and was infected with “hill fever,” transforming them into a feral, flesh-eating monster. The stories of hill fever also coincide with a local First Nation myth about a magical being wearing “the face of the wolf.”

Blake is bitten by the Wolf Man early into their trip, and his wolfy transformation begins almost immediately. There is no myth, no magic, no full moon connection. As far as the film dramatizes, the Wolf Man curse is entirely biological. If there’s any curse, it’s of the metaphorical variety, symbolically representing the curse of neglect and violent woods-bound upbringing that Blake experienced as a boy.

The modern curse

Frankly, it’s a good thing that “Wolf Man” removed a magical “curse” from the werewolf ethos, as it always contained an element of racist exoticism. “Werewolf of London” was about a white guy discovering the exotic dangers of Tibet. “The Wolf Man” was about a white guy discovering the exotic dangers of the Romany people. In many other werewolf movies, the creature is a curse carried into the Caucasian world by First Nation magic. Many of these Wolf Man movies depict a world where white people are safe in cities, and where magical curses all originate from threatening “outside cultures.” There’s an undercurrent of xenophobia to it.

“Wolf Man” does have an element of First Nation mysticism to it — the “face of the wolf” element mentioned above — but it’s not prominent, and it’s not the explanation for where the Wolf Man disease came from. Instead, the “hill fever” is seen as 100% biological in origin, and transmits via wounds. Whannell’s “Wolf Man” is a secular monster film, rejecting both moon magic and the fear of other cultures. By turning the “curse” into something metaphorical, it (ostensibly) makes the story more interesting for a widespread, secular audience.

Whannell, horror fans may know, also made an “Invisible Man” reboot in 2020, and both his neo-monster movies lean just as hard into the “Man” part of the title as they do the “Invisible” and “Wolf.” “The Invisible Man” is about a male stalker, trying to manipulate a girlfriend he was emotionally and physically abusing, and keeping prisoner in his house. “Wolf Man” also takes a very traditionally masculine element of American culture — hunting and survivalism — and turns it into something beastly. It’s a clever approach.

“Wolf Man” is in theaters now.

Leave a Reply